The National Audit Office investigated the construction of the Mater Dei Hospital. I use the word ‘investigated’ because they did. Investigation may have been their intent but at least in so far as the report repeatedly finds huge gaps in the information the office managed to gather, what the report appears to have determined is that the NAO can’t be sure if everything was done right. Or if it wasn’t.

Some perspective first. The NAO were given an incredibly difficult job by Edward Scicluna. He asked them to investigate the financial conduct of the hospital building project since it was still a twinkle in the milkman’s eye some time in 1990.

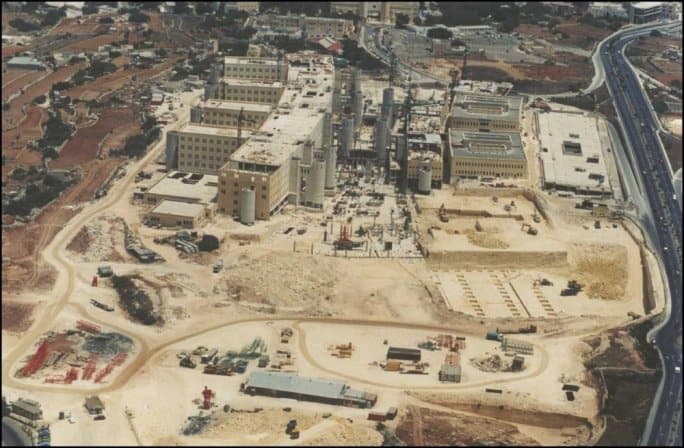

The project was completed in 2011, though the hospital had been opened for business since 2007. So the auditors were asked to investigate a 21 year period that ended 7 years ago, to verify all was done correctly and that value for money was secured.

Quite frankly we should now have an audit to investigate whether the Minister’s request to have this exercise undertaken, which appears to have taken up 3 years of the NAO’s time, was in and of itself worth the cost; if anyone could reasonably expect such an audit at least on matters that occurred in the last century to be of any use beyond historical curiosity; if this was a fishing expedition to see if any people still in politics in 2015 could be usefully smeared ahead of what was at the time expected to be a 2018 election; if the NAO was thrown this incredibly impossible needle in a haystack exercise to distract it from more relevant and more useful contemporary investigations it ought to be conducting.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m never one to argue against learning from history. But it seems to me that the limited oversight resources of the state should not be consumed in effectively academic exercises.

For yes it is academic to debate now whether choosing the San Raffaele model in 1990 was the right choice or not. That decision was reversed all of 22 years ago now. Reviewing the documentation of that discussion from a time an entire generation of voters today were not even born is a matter for historians not national auditors.

I don’t know if that would have been the right decision or not. And I look forward to Joe Pirotta getting to volume 23 of his epic history series he just published a spectacular fourth volume of. But seriously, how is this helpful to public administration right now?

The report discusses how the actual scope of the completed project in 2011 wasn’t even imagined by those setting it in motion in 1990. In between the government changed twice. In 1996 Alfred Sant, who at the time of his election had not yet decided whether to abandon his solemn electoral promise to knock down all that had been built by then, completely re-dimensioned the project. In 1998 when Eddie Fenech Adami replaced him, again, the project was rejigged entirely.

Quite frankly any audit of anything that happened before 1998 is not actually a proper audit of the same project we recognise today as Mater Dei.

Moving on to the second half of the project. Huge gaps in documentation from this period are extremely unsatisfactory, reasonably suspicious and as the NAO put it a gross institutional failure.

There can be no doubt that with all the good intentions of the world, assuming absolutely no one from top to bottom sought personal gain from the delivery of the project, an initiative of that scale will be loaded with mistakes the public administration should have learnt from.

A project of that scale does not happen often and certainly the Maltese public sector has little experience in delivering something that big. There will have been many mistakes and many lessons to learn in procurement processes, contract management, negotiations, pricing, cost controlling, quality assurance and much, much more.

But do we wait until 2015 to start looking into the mistakes that may or may not have happened in 1998 or 2008? Is that how things work here?

Why was the business of the ‘foundation’, whatever that is, that built the hospital not audited while it was still on-going or at least immediately the work ended? That is a criticism to a government I worked for which was keen to deliver a hospital that was an imperative political priority that took too long to complete.

But, and here’s the big but, elected officials and their staffers have a set of priorities that are measured by what they manage to deliver within a single electoral term.

The reason we have autonomous institutions and the civil service is to have sufficient resources to ensure there is institutional memory that survives the change of a government and that ensures the experience of one administration, right or wrong, highs and lows, is of benefit to all others that follow it.

Why did the NAO wait until the Minister decided this was a project worth looking at in 2015, two years into his own term, before it actually checked of its own accord whether records of massive financial transactions were being properly kept, never mind finding out what those records actually said?

That is one additional lesson learnt from this report. But it is not one the Labour Party is interested in.

It was only really interested in looking at how this report could be used to divert attention from the rot and corruption within its ranks by having us talk of our vague recollections of the turn of the century. Out of this massive 3-year exercise of what appears to be complete futility, Labour found the opportunity to tease Clyde Puli who is secretary general of the PN now and worked in the communications office of the foundation that built the hospital in the last few years before it got ready.

Is that all we’re going to learn from a 3 year review of a 21 year long project that ended 7 years ago?

What a waste.