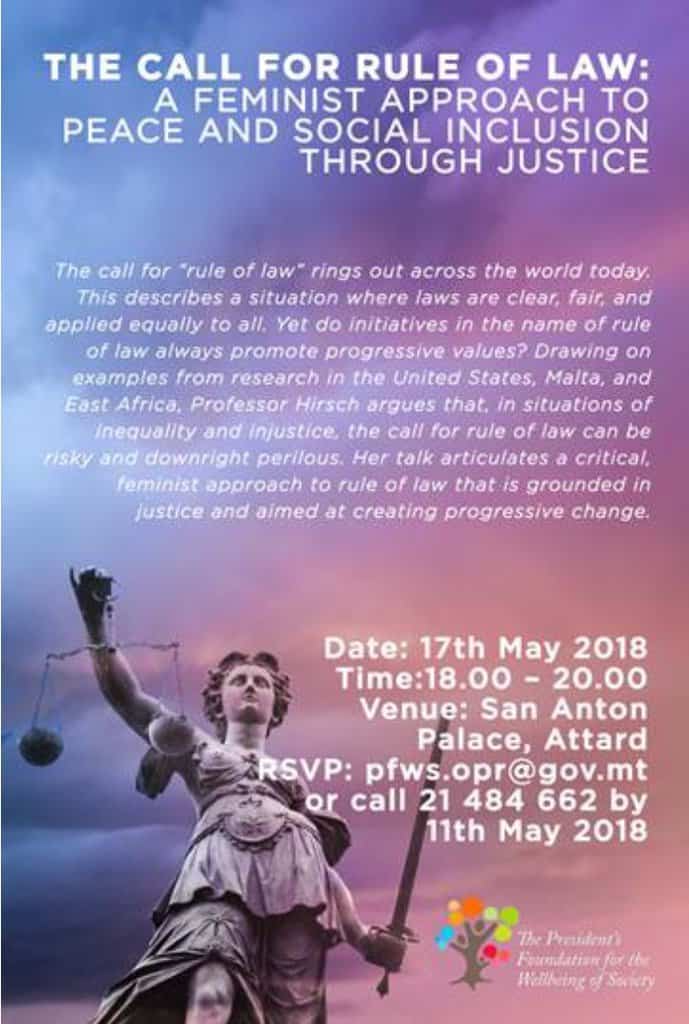

The author of this piece, known to me, reacted to this poster circulated by a quango set up by the President that will be discussing something called ‘a feminist approach to rule of law’.

Not in my name

I was intrigued to learn of a forthcoming event organised by the President’s Foundation for Social Wellbeing on “The call for rule of law: a feminist approach to peace and social inclusion through justice”. My heart skipped a beat, for I thought that finally, H.E.’s good offices have acknowledged the Elephant in the Palace and found the moral courage to address it. My euphoria was short-lived as I went on to read the small print. Being no legal beagle, my learned friends will have to bear with me, but I found three things particularly disconcerting.

The first is a description of the rule of law as a ‘situation where laws are clear, fair and applied equally to all’. Yes, perhaps an event poster cannot be too elaborate. Yet in the current context, it is disingenuous to reduce the rule of law simply to equal treatment. I hope that in true feminist tradition, the presenter will speak truth to power, and point out that first and foremost, the State and its organs and officials are all subject to the law, and that there should be no room for fear or favour. For anyone. Anything less than this would be banal.

The second is even stranger, where we are asked whether ‘initiatives in the name of rule of law always promote progressive values’. What on earth would these ‘initiatives’ be; the rule of law is formal and procedural. Which values are ‘progressive’ is essentially contested, and making a substantive expectation of the rule of law in this way, opens it up to political competition over which ideals the law should pursue. Even within the feminist camp alone, there are sufficiently diverse opinions as to make this meaningless.

Yet it was the third that got me most. ‘In situations of inequality and injustice, the call for rule of law can be risky and downright perilous’. It is precisely in these situations where the rule of law must be called for. All too often, it is the failure of those holding power and privilege to respect and submit to the law that creates inequality and injustice in the first place. The peril does not lie in calls for the rule of law, but in blatantly ignoring them. Of course, that’s not to say that the substance of the law does not matter, or the ways in which it is developed and implemented could not be improved. However, in the current context, the attribution of risk and peril to calls for the rule of law – rather than to a failure to enforce it – seems either naïve or malign, whichever (contestable) version of justice the speaker will put forward.

I won’t be attending this event and perhaps I have prejudged it too harshly, yet if my reading of the strange timing and content is even partially right, then I can only say – as a feminist interested in peace and inclusion – not in my name.